St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude scientists do more with less using PeCan-Seq liquid biopsy

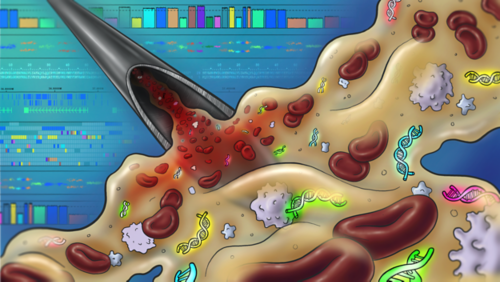

An artistic illustration showing circulating tumor DNA collection for sequencing in the background.

Detecting cancer-driving mutations enables physicians to tailor treatments to the specific genetic makeup of their patient’s disease. But this gold-standard approach isn’t easily accessible. Currently, if physicians want to look for cancer-driving genetic changes, they must take a biopsy of the tumor. This involves putting a patient through a surgical procedure under anesthesia. Research has shown that repeated anesthetic use can have long-term adverse effects on childhood cancer survivors and is also costly and time-consuming. So, investigators have sought other ways to obtain cancer-specific genetic information without the standard biopsy.

Scientists from St. Jude recently published their efforts to address this need. The work resulted in the first pediatric pan-cancer liquid biopsy to detect these mutations from patients’ plasma (a blood component) and was featured in Leukemia. The approach, called pediatric cancer profiling by deep sequencing (PeCan-Seq), can detect all known major pediatric cancer DNA alterations. In the future, an improved version of the technique may replace disruptive bone marrow or tumor biopsies with a simple blood draw.

“We’ve created a promising new potential diagnostic approach,” said senior co-corresponding author Charles Mullighan, MBBS (Hons), MSc, MD, Comprehensive Cancer Center deputy director and St. Jude Department of Pathology member. “It may have advantages in terms of ease of sample collection and potentially reduce long-term morbidity for kids that would otherwise undergo repeated anesthesia.”

Instead of a tumor biopsy, PeCan-Seq works with plasma from patients, sometimes called a liquid biopsy. Plasma contains tumor DNA because individual cancer cells that die will shed their DNA into the bloodstream. This circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from tumors has historically been challenging to detect and sequence in pediatric patients. Findings show the St. Jude researchers have now succeeded, as PeCan-Seq identified genetic alterations from 233 pediatric patients’ plasma cfDNA, but results did vary between cancer types.

PeCan-Seq is a liquid biopsy that detects ctDNA in a small volume

“We genetically fingerprinted children’s cancer from blood samples,” said co-corresponding author Ruth Tatevossian, MD, PhD, St. Jude Clinical Biomarkers Lab director. “It was incredible; we found these DNA abnormalities in the tiniest amount of starting material — just one milliliter of plasma.”

The study was motivated, in part, because oncologists already use this type of liquid biopsy in some adult cancers. However, adult cancers tend to have recurrent genetic lesions, making them easier to detect than those in pediatric disease. In addition, adult ctDNA tests use 10-20 milliliters of plasma, far more than can be taken from pediatric patients.

“Unlike for adults, we can only get a very small amount of starting material from children,” said co-first author Sujuan Jia, PhD, St. Jude Department of Pathology and Clinical Biomarkers Lab. “Working with such a low DNA input was very challenging.”

Ultimately, the group overcame the challenge and reached a robust detection level using 90-95% less starting material while looking for harder-to-detect genetic lesions across cancers.

Perceiving ctDNA with a pan-cancer panel

“I think one of the exciting findings from the study is that we can detect most of the variants we’re trying to at levels approximately equivalent with current flow cytometry-based testing for minimal residual disease (MRD) in the blood,” Mullighan said. “We’re not just detecting disease, but we’re actually detecting the specific genetic changes in that particular child’s cancer.”

Usually, cancer genetic diagnostics target a particular cancer type and are specifically designed for the likely problem genes in that disease. For example, a test may be able to detect single nucleotide mutations but be blind to chromosomal rearrangements.

“A unique part of our method was the pan-cancer nature of our panel,” said co-first author Shaohua Lei, PhD, St. Jude Department of Pathology and Center of Excellence for Leukemia Studies. One of PeCan-Seq’s innovations was finding a way to include genes and DNA alterations across the entire pediatric cancer landscape, creating a more inclusive gene panel and computational pipeline. “With our method, if there are two cancers in a patient, which we had a case of in the study, we can detect both of them,” Lei said.

Improving PeCan-Seq liquid biopsies for the future

While the study was promising, there are still limitations to overcome. The panel robustly detected cfDNA from leukemias, but other cancer types showed less impressive results. For patients with solid tumors, results were mixed, with some being well-detected and others completely undetected. In particular, the test only detected one of 18 brain tumors. However, this study is the first to use PeCan-Seq, so there may be other ways to deploy and improve that test that could be effective for solid tumors and brain cancers.

“I’m a brain tumor specialist,” Tatevossian said. “Now that we’ve established the method, we can try it with other starting materials like cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which may work better to detect tumors within the central nervous system.”

The study was primarily designed to determine whether the PeCan-Seq approach to detecting pan-cancer cfDNA was possible — which it is.

“How much better would cancer screening through a blood draw be instead of going through a CT scan or any complicated, time-consuming or expensive tests?” Jia said.

“I can imagine a test like this in the future,” Lei said. “It would be a low-cost way to improve early detection and help save kids’ lives. We’ve only taken the first step on that path.”