St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Addressing the needs of childhood cancer survivors

Returning home following childhood cancer treatment can appear differently based on environmental factors, healthcare access, and even genetics.

As understanding of the biology of childhood cancer and how to treat it expands, so does the number of childhood cancer survivors. Completing therapy for childhood cancer and transitioning to survivorship is a moment for celebration, reflection and optimism. But once a child leaves the security of St. Jude, where all individuals have access to the same resources, their health care experience can start to differ significantly.

Cancer is an experience that indelibly changes a person — making the idea of simply returning to one’s previous life and the way everything was before unrealistic. The lingering imprint that cancer and its treatment leaves on all survivors, to varying extents, can carry with it complications, increased health risks and continuous re-evaluation that stretches well into adulthood.

Returning home following treatment can mean entering vastly different circumstances depending on where home may be. Childhood cancer survivors often experience barriers to resources such as easily accessed healthcare and healthy foods that are fundamental to a healthy lifestyle. Genetic differences in risks such as the risk of cardiovascular disease for survivors are also often overlooked within research. Additionally, biases and discriminatory practices such as not acknowledging the genetic differences between ethnic groups can be amplified through the lens of survivorship.

St. Jude is taking steps to address these issues to help survivors receive the care they need. St. Jude provides after-treatment care and counseling for all former patients. As a pediatric hospital, this includes annual evaluations until they are 18 years old or 10 years after diagnosis.

“At St. Jude, we have a clinical care model from diagnosis into long-term follow-up that removes some of the barriers of access to care and services,” explained Melissa Hudson, MD, Department of Oncology and Director of the Cancer Survivorship Division at St. Jude. “But as survivors reconnect with community providers, some will face gaps in access to local medical and psychosocial services and resources.

“Services provided by the After Completion of Therapy multidisciplinary staff aim to prepare St. Jude survivors for the transition to adult-focused health care and support them as they navigate the challenges of survivorship in their local communities. This support is also offered to graduates of St. Jude, who may experience new challenges as they get older,” explained Hudson.

The differences in our genetics

Adult care is not where challenges faced by childhood cancer survivors begin, however. For many, the odds are stacked against them due to a lack of appreciation for and research into how biology fundamentally differs from group to group, by the medical research community. This can affect disease development, appropriate treatment, and risks faced after treatment is received.

Yadav Sapkota, PhD, St. Jude Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Control, has interwoven his keen interest in inherited genetic variation into his survivorship work.

“When we think about our evolution, everybody’s ancestry begins with Africa. And from there, we migrated, becoming different clusters. So now what we see in terms of DNA is variation,” Sapkota explained. “Most of the time, it’s common and shared between the population. However, there are some variations that are unique to specific populations. For example, some variations that individuals of African ancestry carry may not be carried by other ancestral groups, or if they carry the same variants, the frequency or the prevalence of that variant may be different.”

The innate genetic variability observed within populations can alter how the body reacts to cancer, as well as therapy. Sapkota explored this phenomenon when he and his colleagues evaluated the gaps in care linking childhood cancer survivors to therapy-related cardiomyopathy, a heart disorder strongly associated with various chemo- and radiotherapies. They found that compared to childhood cancer survivors of European ancestry, those of African ancestry had a 2.5-fold increased risk of cardiomyopathy. This elevated risk is the result after accounting for the known higher rate of cardiovascular risk in the African American population.

“We were thinking if we account for cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and socioeconomic status, then maybe that would render the difference almost nonsignificant. But that did not happen,” explained Sapkota. “So, we still have a greater risk of cardiomyopathy in African American survivors compared to Americans of European descent.”

The importance of representation

“That really pushed us. That’s the reason we started the first-ever study to perform a genetic analysis in African American childhood cancer survivors only.” Sapkota continued. “We found a genetic variant associated with 5.43-fold increased risk of cardiomyopathy in survivors with African ancestry but only 1.31-fold elevated risk in those with European ancestry.”

St. Jude is uniquely positioned to take on this challenge. Being in Memphis, Tennessee, the hospital is part of and neighbored by counties where most of the population is Black. The St. Jude LIFE cohort, established in 2007 to address challenges faced by childhood cancer survivors, is one of the only datasets in the world with the ability to comprehensively represent racial and ethnic groups that are often left out of childhood cancer survivorship research due to a focus on study participants of European descent. By casting a wider net, St. Jude LIFE provides a more robust cohort for survivorship research.

For Sapkota, this begins with genome sequencing. The Human Genome Project allowed researchers to trace perceived genetic risks in humans for the first time, allowing for novel therapies to be developed to combat these risks. However, the datasets used in the Project were largely from individuals with European ancestry, meaning it has a homogeneity problem. Researchers are now playing catch-up and, on the way, learning how diverse the genome can be across populations and how these differences affect disease diagnosis and treatment.

A growing pool of bias

Data availability is often a driving force behind what research projects get done and which questions scientists study. More often than not, what is accessible is what gets worked on. The fact that genomic datasets representing solely or mostly European-ancestry are more widely available means more research is likely to focus on those with European ancestry. This fact keeps Jasmine Plummer, PhD, St. Jude Department of Developmental Neurobiology and Center for Spatial OMICs director, up at night.

“Since 2016, we had an 81% increase in genetics studies, and 85% of this 81% increase is in European ancestry. We’ve essentially plateaued on all the other ancestries. We’re not even targeting the right things, and there are so many levels to that,” proclaimed Plummer, a co-investigator on the African Caribbean Single-Cell Network. The data she references comes from a 2019 paper in Nature Genetics, which demonstrated the harrowing extent of the genomic sequencing gap across different populations.

“The first Black Caribbean prostate cancer cell line was made from scratch by Simone Badal McCreath, PhD, a Jamaican scientist, because there’s a high incidence of prostate cancer there yet no representative cell lines. Her reasoning was, ‘Well, we could be struck by something fundamentally different on the origins of their cancer,’” Plummer said.

Badal, a cancer researcher based at the University of the West Indies, recently authored No Cell Left Behind: A Jamaican Scientist’s Breakthrough to the First Caribbean Cell Line, ACRJ-PC28. This book documents the journey to the cell line’s development, originally published in 2022 Cancer Research Communications.

“There could be drugs that we don’t even need to develop that may be more effective for ethnic groups underrepresented in genomic datasets based on ancestry because there are fundamental differences in the genomes,” Plummer said. “We don’t even have a good understanding of that yet because most drugs have not been tested on cancer cell lines across diverse ancestries.”

Plummer knows that mapping to a reference genome primarily made up of data from those with European ancestry is a recipe for hugely disparate views on health care.

“When we think about how we study survivorship, we must be inclusive and really engaged with the global population. We need a deeper level of understanding, which is a call on us researchers to be inclusive in how we think about the models, how we vet the models and how we adopt the models to other ancestry types,” Plummer emphasized. But such work requires specific, dedicated effort. Until researchers actively push against the trend of Euro-centric data, change will come slowly — one cell line at a time.

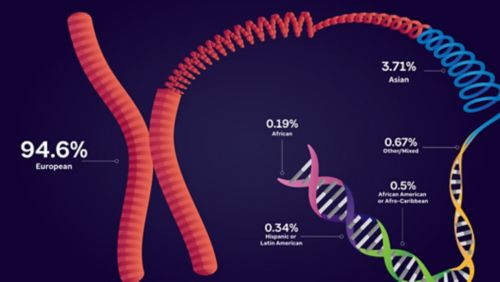

Genomic datasets representing solely or mostly European ancestry are more widely available, meaning more research is likely to focus on those with European ancestry. Data from https://gwasdiversitymonitor.com/ Artwork by Briana Williams.

Flipping the script in clinical care

While the realities of genomic variability and the gaps in care it drives within populations of childhood cancer survivors are beginning to be appreciated, it is not currently feasible for each patient who receives treatment also to undergo comprehensive genomic screening for inherited risks. Caregivers rely on information gathered from the patient or the patient’s family to help ascertain whether there is likely an increased risk of health effects based on inherited variants later in life. As founding chair of the Health Equity Working Group within the St. Jude Cancer Control & Survivorship Program, I-Chan Huang, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Control, is changing how clinicians interact with patients from the moment they walk in the door.

“During the acute phase of their cancer, the treatment is the highest priority, making sure they can receive the correct treatments so that they have better survivorship outcomes. After completing the therapy, patients reintegrate into their community and then issues arise,” explained Huang, who has a health policy and management background. “Their environmental influences on health begins to factor in, such as food insecurity, housing instability, utility insecurity, poor lifestyle, volatile neighborhood and lack of a primary care doctor for follow-up care. People who live in underserved rural areas don’t have as many resources. They must travel to different cities to receive care, which can often be difficult.”

Environmental factors play a huge role in cancer survivorship. In research appearing in JAMA Network Open in 2023, members of the Health Equity Working Group led by Matthew Ehrhardt, MD, MS, St. Jude Department of Oncology, found that childhood cancer survivors who lived within the most disadvantaged neighborhoods such as those with lower education attainment, higher unemployment, and lower income were at a seven-fold significantly increased risk of all-cause and health-related deaths. Huang and his team are exploring ways to combat this before the patient even finishes treatment, but their work, too, is limited by the availability of data.

“There are a lot of problems we need to resolve regarding the infrastructure to take a deep dive into this area. The major problem we are facing is we don’t collect sufficient environmental exposome data from pediatric cancer patients and survivors,” he said. “If we want to look at the personal socioeconomic status among cancer survivors, we only systematically gather information on education, income and insurance, those three key variables. We don’t have the full picture.”

Learning by listening to survivors

As research into childhood cancer survivors grows and matures, a future does exist where, for each individual, caregivers know the potential genetic risks and can create a detailed and accurate description of socioeconomic risks at home. Understanding the risks is just the first hurdle, however. Counteracting those risks would make a significant difference in the lives of survivors.

“In clinical care, I’ve become more mindful that I can’t just recommend specific actions or behaviors because they may not be feasible for all survivors,” explained Hudson. “Do they have a safe place to exercise, access to healthy and fresh foods, or do they have insurance? I’ve changed how I counsel patients. I start first with understanding what their resources are, their out-of-pocket expenses for health care and what other financial demands the family is facing related to accessing cancer-care resources.”

To tackle the challenges that people face once they have completed therapy for childhood cancer, Hudson is keenly aware it takes more than genetic research advancements and clinical practice changes. Large-scale advocacy and education are key to addressing the core problems associated with survivorship within communities that lack support and resources. There is still much to learn about these communities' needs and interventions that will work for members.

“In the clinical context, it’s more than connecting survivors with providers. We also need to improve providers’ knowledge about pediatric cancer survivorship and their comfort level in receiving pediatric survivors into their care. Pediatric cancer survivors are still a rarity in general community practice,” Hudson explained. “Policies that help assure care and educational efforts are key. Integrating survivorship topics into graduate medical education training programs is an important step to increase this awareness. But we also need targeted studies that creatively engage with communities comprising ethnically marginalized groups to partner with researchers so we can better understand their survivorship experience and challenges.”

At St. Jude, investigators are dedicating resources, thought and care toward addressing the realities faced by childhood cancer survivors.

“It requires studies like the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study and other international studies. Such cohorts provide substantial patient-level information to help characterize risk,” expressed Hudson. “Historically, survivorship research focused more on medical outcomes but has increasingly expanded to understand psychosocial outcomes like health care access. This is essential to translating our research into meaningful interventions that can improve the quality of survival among diverse survivor populations.”

The disparate nature of the health care system can put huge strains on families that find themselves scrambling to access the necessities of life after cancer. It’s through fundamental research, thoughtful organization of resources, advocacy and political lobbying that these gaps in care can be addressed.