St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

When the only direction is forward: St. Jude patient travels the globe to find first-of-its-kind cure

Maria Tangonan spends time making art in The Domino’s Village at St. Jude during a recent checkup.

If you ask 9-year-old Maria Tangonan the story behind her name, she will shrug and say, “I don’t know.” But her 11-year-old brother, Lance, is quick to explain that “she got a new name when she got cancer because in our culture, if you get sick, you change to a different name so that the virus doesn’t come back.”

“A name determines the destiny of something,” adds Stephanie Uy, Maria’s mom. The power of a name is part of Filipino consciousness in the Ilocano culture (originating in the northern islands of the Philippines), to which the family traces part of their heritage.

When she was born, Maria was named Aspen. But then, at 22 months old, she was diagnosed with stage 4 high-risk neuroblastoma — an aggressive pediatric solid tumor arising from nerve tissues and cells. Facing an uncertain future, the family decided a new name for their daughter would serve as a new beginning as she began chemotherapy.

At the time, no one imagined this new name would one day be associated with the child who would become the first pediatric patient successfully treated with a novel drug combination for high-risk refractory neuroblastoma.

Before she was diagnosed, Maria Tangonan — then named Aspen — spends time on the beach with her mother, Stephanie Uy, and at home in the Philippines.

Before she was diagnosed, Maria Tangonan — then named Aspen — spends time on the beach with her mother, Stephanie Uy, and at home in the Philippines.

Before she was diagnosed, Maria Tangonan — then named Aspen — spends time on the beach with her mother, Stephanie Uy, and at home in the Philippines.

Searching for the best way forward

In those early days of diagnosis — far from home at St. Luke’s Medical Center in Quezon City – the family would watch the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical, The Sound of Music. Every time the musical number “Maria” came on, the little girl named Aspen would start singing.

“She was sickly at that time and would just lay there because she was in pain and couldn’t verbalize it. When we started calling her Maria, she began to have a different energy. She liked the name; she would become so lively when she sang it,” recalls Stephanie.

While Maria embraced her new name, the Tangonan family knew a name alone would not bring a cure. Her initial chemotherapy treatment was followed by surgery to remove the tumor from her adrenal gland. But the disease spread to her bone marrow and blood, and Maria received more rounds of chemotherapy, a stem-cell transplant, radiation and retinoids. Despite this, the cancer persisted.

Maria’s care team wanted to try immunotherapy, but the treatment was unavailable in the Philippines. “We trusted our doctors back home; they were the best of the best,” says Stephanie. “But they told us it would be difficult to bring this treatment to the Philippines because they didn’t know if the facility could support it.”

Maria’s oncologist, Maria Luz Del Rosario, MD, found an opportunity for treatment at another children’s hospital located on the other side of the globe — St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Maria Tangonan sits in a hospital bed with a baby doll while she awaits treatment.

Connecting across Global borders to access care

Unbeknownst to the Tangonans, Rosario was working with St. Jude Global. While Rosario was treating Maria, she followed a treatment protocol for cases of pediatric high-risk neuroblastoma set forth by St. Jude. As Maria’s disease proved resistant, Rosario contacted St. Jude to see if there were other options. There were — on the St. Jude campus in Memphis, Tennessee, USA.

When Rosario proposed the family travel across the world for treatment, Maria’s dad, Mark Tangonan, recalls that this “was the only pathway we had. It’s either move forward or stop; it’s not left or right. Just forward or stop.”

In what felt like the only way forward, Maria, Stephanie and Mark flew to Memphis in September 2019. For the next three months, the rest of the family stayed in the Philippines while Maria and her parents met with pediatric oncologist Sara Federico, MD, Solid Tumor Division director, Department of Oncology, and other care team members at St. Jude.

“When we got here, we didn’t know if she would qualify for any new treatment. It was one of our biggest fears. What if they sent her home? But Dr. Federico said, ‘We’re going to treat her.’”

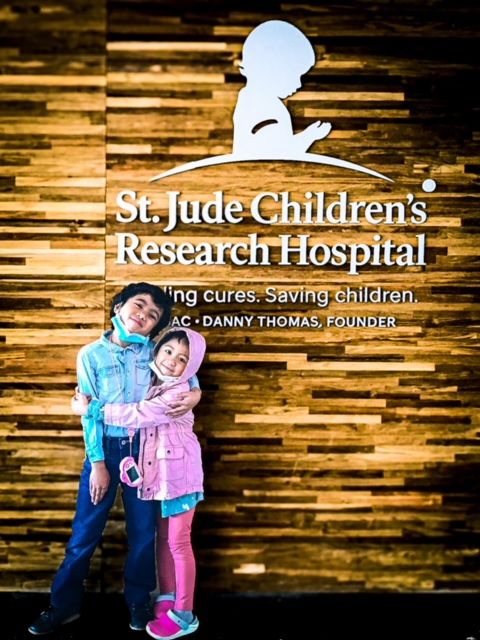

Maria hugs her brother, Lance Tangonan, in front of a sign on the St. Jude campus, happy her brother is with her in Memphis.

By January 2020, the family (Maria, her parents and her two siblings) had fully relocated from the Philippines to Memphis, and Maria began treatment once again. Federico treated Maria for relapsed neuroblastoma using different combinations of therapies that stabilized her disease. But she was still a long way from a cure.

Maria’s best chance at a curative therapy lay in the genomics of her cancer, so Federico requested tumor tissue samples from Maria’s initial surgery in the Philippines for genetic sequencing. When the samples arrived in Memphis, St. Jude researchers identified a germline (inherited) mutation in the BARD1 gene, a finding that gave Federico a new focus point for identifying potential treatments. This process of taking genetic findings and using them to inform clinical care is called clinical genomics.

Clinical genomics gave Federico and Maria a new way forward.

Maria Tangonan with her pediatric oncologist, Sara Federico, MD.

Identifying a new treatment for Maria

A decade of collaborative research in clinical genomics led to the discovery of Maria’s BARD1 mutation. In 2010, St. Jude and Washington University School of Medicine launched the Pediatric Cancer Genome Project (PCGP), a first-of-its-kind collaboration to analyze the genetic underpinnings of pediatric cancer. Through the PCGP, researchers identified germline mutations — inherited genetic variants passed down to offspring through germ cells (eggs and sperms) — and somatic mutations — acquired variants arising in the cancer genome.

Their work resulted in a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine publication that compiled a list of 60 pediatric cancer predisposition gene mutations that became recognized by the oncology community. BARD1 was one of those genes, as were BRCA1 and BRCA2 — two known drivers in adult breast and ovarian cancers.

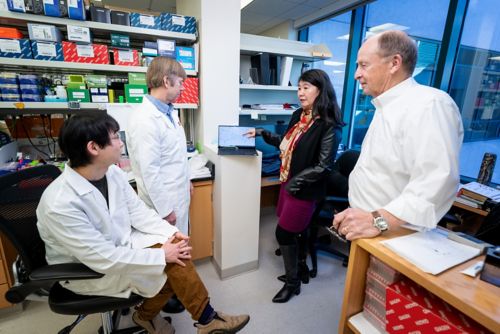

Jinghui Zhang, PhD, and colleagues discuss the use of a patient’s genetic data to inform clinical care.

Jinghui Zhang, PhD, Endowed Chair of Bioinformatics in the Department of Computational Biology, played a pivotal role in the PCGP by helping to place sequencing findings into a meaningful context. “What’s interesting about the BRCA1 or 2 and BARD1 mutations is that they are involved in the same homologous recombination deficiency pathway,” she says.

Homologous recombination deficiency is a problem in how the cell repairs its DNA. Cells have mechanisms for repairing DNA damaged by disease or other factors, but when these mechanisms do not work correctly, damage can pile up. Cancer cells accumulate a lot of DNA damage as they grow. If someone with cancer has a DNA damage repair defect, the tumor will not be able to repair the damage, which can ultimately lead to cancer cell death.

Blocking DNA damage repair by targeting genetic variants that affect the process is a potential treatment strategy for some cancers. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors act on mechanisms in the homologous recombination deficiency pathway and were first used as treatment in adult breast cancer, targeting BRCA1/2 mutations.

“PARP inhibitors prevent cells from repairing these breaks in DNA. If you already have a mutation that causes deficiencies in this repairing mechanism and then the cancer is hit by a drug targeting this, you get what we call a synthetic lethality that causes cancer cell death,” explains Zhang. “This is why germline mutations have been informing therapeutic decisions like PARP inhibition in adult treatment.”

But could PARP inhibitors also be used against pediatric cancers to target germline mutations, including BARD1, that introduce DNA damage repair defects?

Research sets Maria’s next treatment in forward motion

At St. Jude, Elizabeth Stewart, MD, Department of Oncology, had spent years studying potential treatments for Ewing sarcoma, a pediatric solid tumor known to have DNA damage repair defects. In 2014, she published results that demonstrated an Ewing sarcoma preclinical model with a DNA defect had a better therapeutic response to PARP inhibitors when the PARP inhibitors were used in combination with chemotherapy.

Due to Stewart’s work, Federico recognized an opportunity to evaluate this combination therapy approach in other solid tumors with DNA damage repair vulnerabilities. Federico developed a phase 1 clinical trial, BMNIRN, to determine the safe and effective dose of PARP inhibitors to use when given in combination with chemotherapies for pediatric patients with recurrent or treatment-resistant solid tumors.

Equipped with preclinical data and the safe and effective dose for PARP therapies in children as determined by BMNIRN, Federico presented the new treatment option to the Tangonan family. Federico was hopeful that targeting the vulnerability specific to Maria’s cancer would be effective. Once again, it was either forward or stop. “This was the way forward,” says Mark.

Maria and her dad, Mark Tangonan, take a moment in between appointments at St. Jude and pose for a selfie in the Kay Café.

Federico wrote a new treatment protocol specifically for Maria. She began treatment with the PARP inhibitor talazoparib and the chemotherapy irinotecan. The cancer in Maria’s bone marrow quickly responded. She was able to stop chemotherapy after six cycles of treatment, but she continued to receive the PARP inhibitor. She also received radiation therapy for three bone lesions, all of which responded successfully.

She has been completely off therapy since October 2021. To Maria, it feels “free.”

“Maria came here when she was 3 years old, but six birthdays later, she’s in the third grade,” says Federico. “Some could say she just got lucky, but I don’t think that’s it. Her cancer had a targetable problem, so we gave her a targeted therapy. She has been healthy and off treatment for over three years, and now our visits focus on what she is learning in school, talking about her friends and looking at her art.”

The science behind a cure

When Maria responded to treatment, she was the first child with refractory high-risk neuroblastoma to have a durable response to a PARP inhibitor and chemotherapy combination.

Maria Tangonan, with her sister Kai Tangonan, explores art as a creative outlet.

To understand why, Federico turned to Zhang and her team to dig into the genomic data from Maria’s case. As experts in analyzing and understanding genomic data, Zhang’s team was well-positioned to run the necessary genomic analyses to identify the cellular mechanisms that explained Maria’s positive response.

“Identifying the variant comes first, then there is the clinical care, and then we retrospectively try to understand the response to the clinical care. That’s where cis-X comes into play,” Zhang explains.

Cis-X is a computational method that identifies noncoding genetic variants responsible for gene function. Using an allele-specific expression technique developed for the cis-X program, the researchers verified that both copies of the BARD1 gene (one inherited from each of Maria’s parents) were missing, an occurrence called a biallelic loss.

A biallelic loss causes a complete loss of function for the gene overall. So, Maria’s missing BARD1 gene explains why she responded so well to the PARP inhibitor administered in combination with chemotherapy. “This case will inform others considering treating pediatric patients with PARP inhibitors,” says Zhang. “I believe that losing both copies of the BARD1 gene will be important for achieving a durable treatment response because losing only one copy is insufficient.”

The success of Maria’s treatment shows the potential not only for PARP inhibitors as targeted treatments in pediatric refractory solid tumors but for the use of clinical genomics as part of regular clinical care.

Maria Tangonan dances in an outdoor water fountain as she takes a break from treatments at St. Jude.

Beyond Maria’s success — moving forward, not stopping

“I’m thrilled by these results because it’s so rewarding for me to see Maria cured of her disease due to the findings from clinical genomics,” says Zhang. “This is one of the most rewarding projects I’ve ever participated in.”

As data analysis capabilities continue developing, Zhang sees a future for clinical genomics that integrates germline and somatic variant data into therapeutic decision-making. Maria’s case, published in 2024 by the New England Journal of Medicine, stands as a first-of-its-kind feat in pediatric oncology and clinical genomics. But it will not be the last.

Researchers continue to lead clinical trials of targeted therapies for difficult-to-treat solid tumors, using what they learned from clinical genomics and Maria’s care to inform the next generation of studies. One such trial, led by Federico, is ONITT — a phase 1/2 study evaluating a combination of PARP inhibitors and a liposomal chemotherapy formulation in children and young adults with refractory solid tumors and Ewing sarcoma.

While the science advances and research continues, Maria and her family revel in a life without treatment. The family still comes to St. Jude for checkups every six months to monitor the disease and mitigate any treatment-related symptoms that may arise. But for Maria, moving forward also means not leaving Aspen, her birthname, behind. While she prefers Maria, she says Aspen is just part of her full name now.

Throughout her entire life, Maria Tangonan has relied on art and family as her means of expression and support.

Throughout her entire life, Maria Tangonan has relied on art and family as her means of expression and support.

Throughout her entire life, Maria Tangonan has relied on art and family as her means of expression and support.

Maria Aspen Zanne Tangonan wants to continue to be a girl “who travels the world.” For a family whose only direction was forward as they traversed the globe in search of a cure, anything seems possible.