St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

There from the beginning: The evolution of HIV research and care at St. Jude

St. Jude has had an HIV research and care program since the virus first emerged in the early 1980s, learn about the work – then and now.

St. Jude Social Worker Chris Sinnock, LCSW, remembers the patient exactly: the first of several individuals treated for cancer, returning to St. Jude suffering from a strange, persistent pneumonia. More than four decades later, these memories have stuck with Sinnock. It was the start of what would become the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

“I remember this patient looked at me and said, ‘You were my social worker when I had cancer; are you still my social worker now?’ that was what launched me from oncology into HIV work,” Sinnock said.

St. Jude Social Worker Chris Sinnock, LCSW, has spent the four decades since HIV first emerged working to support St. Jude patients and families navigating HIV.

St. Jude has researched and cared for patients with HIV since the virus first roared to life, creating a need for better understanding and dedicated care. For someone who doesn’t know St. Jude very well, it may seem like an odd fit. But not if you understand that the immortal words of St. Jude founder, Danny Thomas, that “no child should die in the dawn of life” shapes every action St. Jude takes. No child.

But it wasn’t just Thomas’s vision that spurred St. Jude to develop a program for HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. It was the dedication and willingness of St. Jude faculty and staff to care for this mysterious illness, to stick with their patients, to ask what they could do to help the Memphis community, to step up when there were more questions than answers. It was the willingness of patients and their families to participate in research, to partner in finding a way forward.

Today, the HIV program at St. Jude leads clinical trials testing therapies while providing the support patients and their families need to thrive. From what was once a death sentence to living full, healthy lives — the St. Jude HIV program has been both an innovative force and a reliable presence patients can count on.

Early days of HIV at St. Jude

While St. Jude researchers are best known for their work on childhood cancer, studies of oncology and infectious diseases have gone together for as long as the hospital has existed. Children with cancer are at increased risk of infections because their disease and its treatments can leave them immunocompromised.

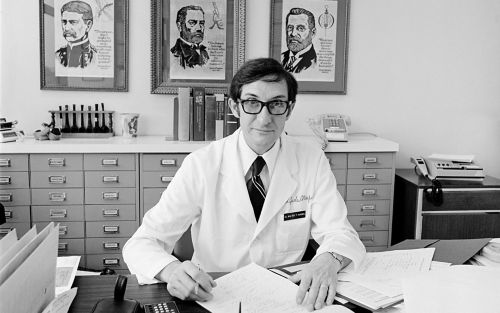

Walter Hughes, MD, was chair of the St. Jude Department of Infectious Diseases when HIV first emerged, and he led the hospital’s response to the virus.

The late Walter Hughes, MD, helped establish the St. Jude Department of Infectious Diseases and served as the department’s chair from 1969–1977 and again from 1981–1995. Hughes led the hospital’s initial response to HIV.

Patricia Flynn, MD, Arthur Ashe Chair in Pediatric AIDS Research, St. Jude Department of Infectious Diseases, came to Memphis to complete her pediatric residency in 1981. She stayed at St. Jude for additional training in pediatric infectious disease and was in the first year of her fellowship here when she saw her first patient with HIV. For Flynn, it was a teenager with hemophilia (a blood clotting disorder). In those days, there was no way to screen blood for HIV (which is not the case today), so individuals who needed blood products could be infected by donated blood.

“This was a new disease, with no therapy, and the outcome was uniformly death,” Flynn said. “It was just screaming for people to care for the unusual infections and do the clinical research to find ways to treat these kids.”

Patricia Flynn, MD, Arthur Ashe Chair in Pediatric AIDS Research, St. Jude Department of Infectious Diseases, was a fellow when HIV first emerged, and she ended up dedicating her career to studying and treating the virus.

Both Flynn and Sinnock remember Hughes’s leadership on HIV as dedicated and unwavering. Hughes had already made a breakthrough in treating Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a life-threatening fungal infection in pediatric cancer patients. His work, which was published in 1977 in the New England Journal of Medicine, took on a whole new life due to HIV. He showed that the antibiotic drug combination trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) could prevent and treat PCP. During the emergence of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, PCP was the first opportunistic infection identified. It was the cause of the pneumonia that Sinnock encountered in her patients.

The first antiretroviral for HIV, zidovudine (AZT), was approved in 1987. One of the first studies that Flynn worked on at St. Jude looked at the antiretroviral didanosine (DDI), which in 1991 became the second drug approved to treat HIV.

“Walter always talked about it sort of being modeled off the success in leukemia; even back then you could recognize that HIV would take a combination of medicines to treat, just like cancer,” said Flynn.

In 1992, St. Jude became a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), which later became the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network (IMPAACT), a designation that the hospital still holds 31 years later. Over the years, St. Jude also joined large, collaborative NIH-funded study groups such as the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions and the Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study (PHACS), among others. Through the clinical trial center, the team started to study the virus’s transmission, specifically between mothers and babies.

Supporting mothers and children

In the early days of HIV/AIDS, most patients at St. Jude were babies and their mothers. Hughes, Flynn and their colleagues worked on the ACTG 076 study to demonstrate that treating pregnant, HIV-positive women during pregnancy, labor and delivery could reduce the rate of HIV transmission.

“Realizing that transmission between mother and baby could be stopped — that was a remarkable change,” Sinnock remembers. “Within just a few months’ time, it changed the whole scope of what we were doing with HIV, providing a pediatric program.”

Katherine Knapp, MD, medical director of the St. Jude perinatal HIV program focuses her work on mothers and babies with HIV.

Today, if a pregnant woman who is HIV positive is on the proper medication, there is less than a 1% chance that the baby will be born with HIV. There are still 40-50 infants born to HIV-positive mothers in the Memphis area each year, but the flood of patients has become a trickle, with just one positive infant every other year or so. This is partially due to third trimester testing for pregnant women to identify those who do not know they have HIV. That testing enables early treatment of infants born to mothers who were HIV positive and not on therapy.

“For some genetic diseases, there is a much higher risk of the baby getting the disease than of a baby getting HIV from a mother who is on therapy,” said Katherine Knapp, MD, medical director of the St. Jude perinatal HIV program.

HIV landscape shifts toward adolescents

Through cooperative groups and industry studies, St. Jude has long been a test site for medications to treat HIV and has played a role in getting approvals for pediatric use.

“If you look down the list of drugs approved for pediatrics, we worked on many of the clinical trials to get them approved,” said Flynn. “I think that’s probably the biggest accomplishment we’ve had.”

Protease inhibitors, which target a protein HIV needs to replicate, were approved in 1995 and shifted the landscape of HIV care. Those drugs changed the conversation around HIV because, for the first time, patients could live a normal lifespan.

As the years went by, the demographics of those who were HIV positive shifted away from infants and towards adolescents and young adults.

Knapp is the St. Jude principal investigator for PHACS, which opened its first clinical trials in 2007. Through PHACS, St. Jude participates in two long-term studies called Surveillance Monitoring for Antiretroviral Therapy (SMARTT) and Adolescent Master Protocol (AMP/AMP UP). SMARTT studies mothers who are HIV-positive and have babies who are negative. AMP started with children 7-12; the current version, AMP UP, studies individuals 18 and older. There is a group infected as infants and one that was exposed but not infected.

Aditya Gaur, MD, Division of HIV Medicine Director, St. Jude Department of Infectious Diseases, oversees new research on HIV

“Through these studies, we are gaining critical long-term data about the lives and health of children exposed to or growing up with HIV,” said Knapp. “We don’t have a lot of data because many of these children didn’t survive before 20 years ago when we started having better medicines, but now, we can learn if there are any risks for health effects for these kids — from the virus or the medications.”

Treatment today: injectable antiretrovirals and prevention

Aditya Gaur, MD, Division of HIV Medicine Director, St. Jude Department of Infectious Diseases, oversees new research on HIV. Over the years, innovations have led to two different focuses: developing medications that are easier to take and prevention (pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP).

“Over more than two decades, HIV went from being something untreatable to having combination antiretroviral therapy,” said Gaur. “We are lucky to have a number of antiretroviral treatment options, providing safe, effective treatment options which are co-formulated as one pill once a day, at least for youth and adults.”

But even one pill can present a challenge.

“When we think of not just HIV, but any chronic disease, be it diabetes or high blood pressure, people struggle with taking medicine every day,” Gaur explains. “But, add to that, when you have a condition stigmatized in society, where the act of holding a pill or taking a pill in the presence of someone else may be a reminder that you have HIV, then one can see why staying adherent to what is otherwise a simple, potent, safe one pill a day combination can become even harder.”

“Right now, the Achilles heel of HIV treatment is these periodic struggles with taking medications every day,” he adds.

To help address this concern, HIV treatment is turning towards long-acting injectable antiretrovirals. In adults, cabotegravir/rilpivirine is a combination injection of two shots every eight weeks. Gaur is co-chair of a collaborative study called IMPAACT 2017. The study tested cabotegravir/rilpivirine in 12 to 18-year-olds and was used for approval in that age group. Clinical trials on the horizon will study this long-acting combination injectable for children under 12.

Long-acting injectables, which require only one injection every six months, are also being studied in adults.

Nehali Patel, MD, Director of Clinical Services, St. Jude Infectious Diseases Clinic

“Imagine only having to come in to get a shot twice a year and being well controlled with your HIV,” said Nehali Patel, MD, Director of Clinical Services, St. Jude Infectious Diseases Clinic. “We are the first and only institution in the Memphis area doing these trials and giving our patients the benefit of these medications early.”

“I think what excites me the most is this shift to injectables and long-acting medications because you really don’t have the risk of having small blips of viremia,” Patel added. “If you take an oral medication every day and you don’t take it around the same time, you can have dips in your blood levels of that medication, and the virus can start replicating, making it possible to transmit the virus. But with these long-acting injectables, the virus is suppressed for long periods. I think that is the key, really, to preventing new infections and helping patients stay undetectable.”

Preventing infections through PrEP is also a game-changing endeavor to protect individuals at an increased risk of contracting HIV. St. Jude recently participated in a multi-center study led by the HIV Prevention Trials Network called HPTN 083, testing injectable cabotegravir for prevention. St. Jude was one of only three centers enrolling 18 to 24-year-olds. These phase 3 trial results led to the FDA approval of cabotegravir given every eight weeks for HIV prevention.

These innovations demonstrate just how far HIV treatment has come since 1981. With different patient populations and novel therapies, the needs of patients have also shifted, but social work and patient support have kept up.

“Our social work services have shifted alongside the changing landscape of the medications, now we can focus on mental health, on life skills, on how to navigate medical systems and care for themselves,” Sinnock said. “It’s a huge shift from supporting somebody knowing that their life is going to be short to now supporting them to be all that they can be.”

In addition to program support ranging from transportation and food to primary care, school support and psycho-social services, the HIV clinic also now has a strong transition clinic.

“We transition patients to adult care at 24, but before that, we really prepare them, making sure they have the right insurance, changing their medications to an outside pharmacy and giving them all their adult care options,” explained Patel.

Hard-won successes pave the way for a brighter future

In the decades since that first patient with pneumonia reached out to St. Jude asking for help, there have been astounding innovations in the care and treatment of HIV. Many lives were snuffed out by the virus while researchers worked to understand it, advocacy groups fought for funding, social workers and community leaders established programs, and clinicians and patients conducted the clinical trials necessary to bring about new therapies. HIV care today is a testament to the progress that can be made by many individuals pulling together to make change.

St. Jude continues to stand firm in a commitment to people living with HIV. It is the same commitment that has always driven St. Jude.

“The whole purpose of St. Jude is to focus on catastrophic diseases of childhood,” said Flynn. “We had an opportunity to recognize what was certainly one of the biggest catastrophic diseases of childhood in the 1980s and 90s and to make a real impact, and I think with the St. Jude approach to holistic care that married what we were doing in the clinic with social work and support for patients with HIV, we have done that.”