St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Ramilo brings RSV expertise to St. Jude

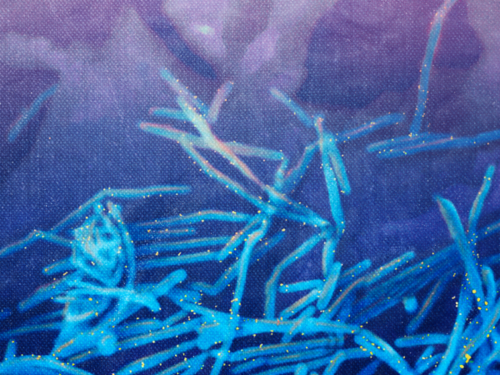

Colorized electron microscopy of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) particles from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

A family carries their infant with a clean bill of health out of the pediatrician’s office. But as they see someone sneeze, they can’t help but tense. There is an invisible, airborne and constantly lurking threat to their young child: respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

“Across the world, the number one cause of hospitalization in the first year of life is RSV,” said Octavio Ramilo, MD, newly appointed Department of Infectious Diseases chair at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “Only malaria causes more deaths than RSV in that first year. That’s why it is the virus that we’ve been working on for the last 25 years.” St. Jude recently recruited Ramilo to lead the Department in addition to continuing his research confronting the pressing need for RSV prevention and protection in pediatric patients.

RSV is tailored to affect vulnerable children

Annually, RSV infects an estimated 64 million people and causes 160,000 deaths, with most morbidity and mortality occurring in the very young. Despite the virus’s prevalence and impact, no effective vaccine or antiviral exists.

“Why is that?” Ramilo asked. “First, young children have a very immature immune system, so they don’t make an effective immune response to the virus. Even when patients get infected with the virus, it doesn’t lead to long-term immunity, and they can have repeat infections. It’s not like measles or chickenpox that you get only once.” This lack of an effective immune response makes traditional vaccination strategies nonviable, as they require a robust immune response to work.

“Second, these young children have airways that are small, so when they get inflamed, it causes a lot of problems. That’s why they cause respiratory compromise easily,” Ramilo said. “Third, the virus is unique with a gene called non-structural gene 1 (NS1) that blocks the antiviral immune response of the child. RSV developed the perfect setup to affect young children that are more susceptible, such as those that are immunocompromised.”

Launching research to prevent RSV infections

To protect vulnerable children, researchers must find a way to prevent RSV infections. Infants only begin making their own antibodies to fend off infection 5-6 months or more after birth. Before then, they have an ever-diminishing supply of maternal antibodies, which lapse before the child can make their own. This waning of maternal immunity and slow development of childhood immunity makes infants particularly susceptible to RSV’s ability to escape the immune system.

Current clinical trials focus on vaccinating mothers to increase the amount and duration of those maternal antibodies. Additionally, other trials will explore passive immunization, where a clinician gives children anti-RSV monoclonal antibodies until they can make their own.

With the arrival of Ramilo, St. Jude is joining the search for strategies to tackle RSV in a robust way. The unique population of St. Jude patients, which includes many immunocompromised children, makes RSV an ever-present threat. Ramilo dedicates his research efforts to understanding how the virus, infant immune systems and vaccinations interact to find ways to protect vulnerable children. His approach is examining how infants respond to infection.

“We’ve realized we needed to study what we call early life immunity,” Ramilo said. “We are now launching a program to more intensively study how babies’ immune systems develop over time when they get infected with this virus.”

“Our next step will be to study pregnancy. We want to learn how pregnancy immunity affects the baby’s immune system because that’s a promising area for discovery that has been understudied in the field,” Ramilo said.

Finding the right fit at St. Jude

St. Jude has much to offer an investigator like Ramilo, who arrived at the institution in early 2023.

“St. Jude has a strong tradition of infectious disease research,” said Ramilo. “There’s a lot of work in influenza, HIV, basic discovery of bacterial diseases and management of infections in immunocompromised children. It was also very attractive to bring my RSV research and expand into the institution’s different areas of expertise, including the basic science, microbiology, immunology, pharmaceutical science and structural biology specialists here. We are especially excited to leverage the deep expertise here in viral sequencing and bioinformatics to study how RSV sequence variation affects disease.”

The merger of St. Jude expertise and resources with Ramilo’s research approach will help advance understanding and discovery around RSV. Ramilo has both a bench science and clinical background. This experience gives him a broad perspective on what is needed to take translate basic discoveries into meaningful clinical impact. He recognizes the tremendous need to find practical solutions for RSV – especially in the immunocompromised infants and children treated at St. Jude. But Ramilo’s goals for St. Jude and the Department of Infectious Disease don’t stop at RSV.

Infectious Disease research moves forward

“We want to expand the depth, but also the areas of interest of the Department,” Ramilo said. “We are currently assessing which areas we should expand beyond respiratory infections and early life immunity.”

“At the same time,” Ramilo said, “we have unique populations in St. Jude that provide in-depth specialized perspectives. For instance, we have significant numbers of bone marrow transplant and cell therapy and cancer patients. We will redouble our efforts to see how we can optimize new therapies in the context of infections in transplant patients. We want to build upon the institutions’ unique strengths in these areas, leveraging our own expertise and collaborating with the well-established research teams at St. Jude.”

Infectious diseases such as RSV remain a threat, particularly to the immunocompromised patients at St. Jude. But with Ramilo at the helm of the Department of Infectious Diseases, St. Jude will continue to make significant inroads in the understanding and treatment of these illnesses — including branching into new fields that leverage novel collaborations.

This research paves the way for a future where parents with young children have fewer infections to worry about.