St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

It’s in the genes: research reveals obstacles on the road to health for cancer survivors

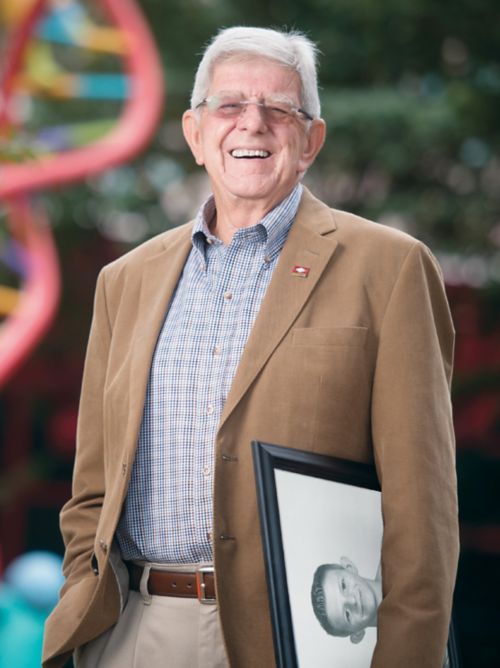

Dwight Tosh, 60 year survivor of childhood cancer.

In 1962, 13-year-old Dwight Tosh and his family were given the terrible news that he had only a week to live. But little did he know that a new hospital in Memphis, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, was innovating treatments for childhood cancer that would change his fate.

Due to care he received at St. Jude, Tosh was recently celebrated for reaching a milestone every child treated for cancer hopes for: the 60th anniversary of his treatment, making him the first St. Jude patient to achieve such long-lasting survivorship.

But while Tosh’s remarkable milestone speaks to the power of cancer treatment, his health journey has had many detours and obstacles along the way.

“Over the course of my lifetime I have experienced a few health problems,” Tosh said. “A second cancer. Heart issues. Joint problems. Diabetes.” This matches the experience of other survivors. After receiving their childhood cancer treatment, they continue to have a difficult health journey throughout their adult lives.

St. Jude scientists have been studying the unique vulnerabilities and diseases of adult childhood cancer survivors. Certain treatments cause heart damage and other effects. Lifestyle also influences the development of chronic conditions. But treatment and lifestyle factors alone are not enough to explain the disproportionate rates of chronic disease in survivors. There is growing evidence genetics play a major role.

Yadav Sapkota, PhD, Epidemiology and Cancer Control, is a leader in the genetics of survivorship. He collects and analyzes data from childhood cancer survivors to identify genetic variants associated with increased risk of chronic conditions and other diseases.

Sapkota can do this research because Tosh and other survivors participate in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (St. Jude LIFE). Thousands of childhood cancer survivors and hundreds of healthy individuals who serve as a control group for comparison come to St. Jude throughout their adult lives for regular health screenings. They also have their whole genome sequenced, providing a rich trove of genetic data.

Sapkota’s goal is to find genetic variants in this data that predict health risks in childhood cancer survivors so patients and their families can act accordingly to prevent disease

Yadav Sapkota, PhD, Epidemiology and Cancer Control

Predicting obesity risk in childhood cancer survivors

In a recent study, Sapkota found that childhood cancer survivors have an elevated risk of developing severe (morbid) obesity as adults (body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or higher). Sapkota’s group created a tool, combining genetic information, clinical outcomes and lifestyle factors, that can predict which children are at the highest risk of developing severe obesity as adults.

“It is important for childhood cancer survivors to know if they are at risk for developing various chronic conditions,” said Sapkota, the first and co-corresponding author of the research published in Nature Medicine. “We have developed a prediction model that can help health-care providers identify which survivors are likely to develop severe obesity.”

In the study, survivors with the highest genetic risk scores were at 53 times greater risk of developing obesity compared to survivors with the lowest genetic risk score. These scores were independent of other non-genetic risk factors.

By using this tool at diagnosis, physicians could help families adopt healthy diet and exercise habits for patients at high risk of developing obesity as adults, but the tool needs to be further validated before being used in the clinic. It will also require whole genome sequencing to become part of the standard of care for childhood cancer patients. Whole genome sequencing is currently prohibitively expensive, but scientists are searching for ways to reduce those costs.

The hope is that genetic risk scores, such as the one created in the study, can become a regular part of clinical care.

Drug and DNA variant don’t mix in childhood cancer survivors

Adult childhood cancer survivors often experience treatment-related toxicities and other late effects. Scientists have long known that childhood cancer survivors have a higher risk of developing heart disease. However, not all survivors develop cardiac problems, even those who received the same treatment.

With revolutions in technology, researchers can now better attribute the source of this difference in cardiac disease. Sometimes, specific genetic variants and cancer treatments combine their effects in ways that increase heart disease more than either alone.

Sapkota identified a genetic variant, that in the context of childhood cancer treatment using the chemotherapy doxorubicin, greatly increased the risk of adult heart disease. He published the results earlier this year in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“We see that cardiotoxicity risk is much higher in someone who carries at least one copy of this particular variant,” Sapkota said. “With just a single copy, a survivor will have a 3-times larger risk of developing cardiotoxicity compared to someone else who does not have it.”

“But if somebody carries two copies of the variant,” he added, “then, that person will have a 9-times higher risk for development of cardiotoxicity compared to those who did not carry the allele.”

He found the connection in the St. Jude LIFE data and validated the finding in a separate group, the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. The relationship between the genetic variant, doxorubicin and elevated risk of cardiac dysfunction was present in both people of European and African ancestry. This consistency in people of different ancestry is rare in genetic research, indicating a strong effect. The

variant, near gene KCNK17, has never before been implicated in cardiac disease. It’s now the focus of a flurry of research activity. Scientists hope to understand its underlying biology and develop treatments.

Childhood cancer survivors have a genetic risk of stroke

Like heart disease, childhood cancer survivors are also at high risk of stroke. Conventional wisdom in cancer care until recently blamed certain treatments, especially cranial radiation for this increase in risk. This claim had some validity but did not explain why patients treated with the same therapies had different stroke risk.

The St. Jude group found the source of the difference was a single genetic variant. Sapkota found the genetic variant is associated with at least three-fold increase in stroke risk in patients treated with cranial radiation, though those treated with an intermediate dose experienced a five-fold risk increase.

Together, the radiation and genetic risks explain why high radiation doses are partially correlated with stroke risk, but do not completely explain stroke incidence. The findings were announced at a press conference as part of the American Association for Cancer Research annual meeting in 2019 and published in Clinical Cancer Research.

“Ultimately our findings help determine who is at a greater risk so we can intervene on modifiable lifestyle and other factors that are known to affect the risk of stroke,” Sapkota said.

Zhaoming Wang, PhD, Epidemiology and Cancer Control

Premature epigenetic aging in childhood cancer survivors

In addition to Sapkota, the St. Jude Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Control is home to other researchers committed to improving the lives of childhood cancer survivors. One such researcher is Zhaoming Wang, PhD, who holds a cross-appointment in the St. Jude Department of Computational Biology. His work lays the foundation to understand why certain childhood cancer survivors develop chronic diseases commonly associated with a much older chronological age.

In a recent study, published in Genome Medicine, Wang’s group performed the first analysis that identified genetic risk factors underlying accelerated aging in survivors.

“This is one of a series of studies my lab has undertaken to investigate aging biomarkers in childhood cancer survivors,” Wang said. “We previously evaluated non-genetic risk factors including cancer treatments, health behaviors and chronic health conditions that contribute to age acceleration. This study focuses on the underlying genetic factors among these patients.”

The researchers tested 8 million gene variants and found two associated with epigenetic age acceleration in patients. Epigenetic age acceleration is a measure of the difference between “biological” and chronological age. Importantly, epigenetic age acceleration strongly correlates with the development of what are normally considered age-related diseases, independent of chronological age.

The identified variants may allow physicians to find the survivors at highest risk of accelerated aging before they develop symptoms and begin preventative interventions. The findings have also galvanized a search for drugs to target the affected genes.

Conclusion

From obesity and heart disease to stroke and accelerated aging, genetics have a major impact on chronic disease risk in childhood cancer survivors. The key to finding these genetic variants are generous childhood cancer survivors, such as Tosh, who participate in research studies such as St. Jude LIFE. Using this rich dataset, Sapkota, Wang and others at St. Jude are making discoveries to propel survivorship research forward.

All data used to discover genetic variants in the St. Jude LIFE cohort is freely available to other scientists on the St. Jude Cloud so they can contribute to the growing literature on childhood cancer survivors and ultimately help fulfill the St. Jude mission of improving cancer treatment for these patients.