St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

St. Jude Family of Websites

Explore our cutting edge research, world-class patient care, career opportunities and more.

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital Home

- Fundraising

Science begets science: Betty Mortimer Roberts, PhD

The biomechanics research of centenarian Betty Mortimer Roberts, PhD, revolutionized how hockey players approach the slapshot and how pro football players kick field goals. This scientist and university professor has inspired generations of scientists—including her son, a renowned oncologist and researcher at St. Jude. Pictured is Mark Johnson, star of the Wisconsin hockey team and a future Olympic gold medalist for the 1980 Miracle on Ice team, during a research session on the slapshot.

In the annals of history, scientists are judged largely by the number and impact of their discoveries. For Betty Mortimer Roberts, PhD, that influence extends far beyond her pioneering explorations in the field of human movement. Through her passion for science and seminal contributions to the field, Roberts, now approaching 101 years of age, has served as a role model for generations of scientists, including her son, an executive vice president and director of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Roberts’ story is one of revelation and understatement. She currently resides in a retirement community in Wisconsin where, until the outbreak of COVID, she admitted to swimming laps “only” three times a week. A trailblazer in the biomechanics of sports, she conducted research that—among other achievements—helped a future Olympian perfect his slapshot and bolstered the accuracy and distance of NFL kickers.

Research conducted by Betty Roberts, PhD, showed that a more flexible hockey stick produced more powerful slap shots. It was previously thought the stick did not bend, but her research showed the stick would bend, loading energy, when it hit the ice. Photo by Ben Brewer.

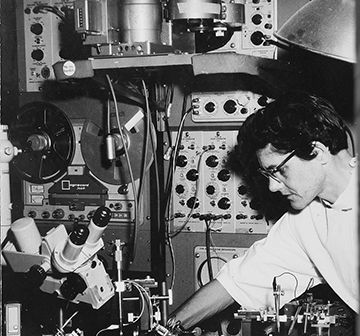

Betty Roberts, PhD, in the lab.

A native of Toronto, Roberts began studying the mechanics of human movement as a girl. When her mom, a non-swimmer, described how to perform the breaststroke, 8-year-old Betty listened carefully and then calculated the most efficient techniques required to master that stroke. More than a decade later, she would become the University of Toronto’s intercollegiate breaststroke champion, and subsequently earn a place in the institution’s Sports Hall of Fame for her prowess in swimming, basketball and ice hockey.

After serving in the women’s branch of the British Army during World War II—where she drove military trucks, served in the Army of Occupation in Austria and Italy, and won the Canada Honour Award—Roberts enrolled in graduate school. There, she continued her passion for athletics, wanting to understand how the nervous system generated the remarkably complex movements that underlie elite sport activities. Her calculations on the optimal trajectory for shooting a basketball from various locations served as the basis for her master’s degree as well as her first journal publication.

“That really intrigued me, because it could explain how the body in sports—let’s say, throwing—can be so exquisitely tuned to develop speed,” she says. “A 100-mile-an-hour pitch? It’s phenomenal. The body must be prepared to do this.”

After earning a doctoral degree in physiology and physical education, she joined the faculty at the University of Wisconsin, where she taught and conducted research for many years. Her research ultimately spanned from pioneering techniques to record impulses from single gamma motor neuron fibers as they entered muscle spindles to filming athletic skills at 200 frames per second.

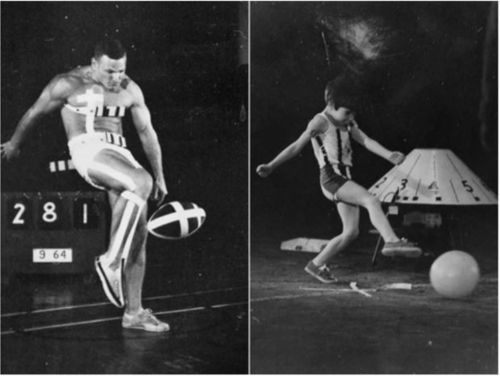

When he was a little boy, Charlie Roberts (at right) took part in research studies conducted by his mom, Betty Roberts, PhD. These studies, which also included adult athletes such as John Hoye (at left), analyzed the mechanics of the kick.

Nature vs. nurture

If there were a how-to manual for becoming a world-renowned scientist, the first chapter might be dedicated to the cultivation of intellectual curiosity. Is a passion for science created through genetics or environment? For Charlie Roberts, MD, PhD, the answer may lie somewhere in between. After all, he has been involved in research since he was a toddler, when he became a willing participant in research, led by his mom’s colleagues, studying the muscular skill development in children.

“From as young as I can remember, I was put through the paces on high-speed film—throwing and kicking and jumping,” he says. “Every six months, they would put me back through and record how I developed.”

He participated in his mom’s research, too. One such study led to the transformation of hockey stick design.

“I was in seventh grade, and I saw my mom in the door of my school motioning me over in the middle of the day,” Charlie recalls. “I walked over, and she said, ‘I've got your hockey bag in the car. Come on.’”

When they arrived at the ice rink, Charlie met Mark Johnson, star of the Wisconsin hockey team and a future Olympic gold medalist for the Miracle on Ice team.

“That was the slapshot study,” Charlie recalls. “I was the control subject—someone who could do a slapshot but was not exceptional. Mark would skate by the camera, and I would skate by. He would do a slapshot, and I would do a slapshot.”

In a 2014 interview, Betty Roberts explained the rationale behind the study.

“What we were doing was calculating the speed of the approach of the stick before it contacted the puck,” she said. “Our cameras back then weren’t really fast enough to capture it, perfectly—it would actually be good to repeat the study now—but the data we collected could then be applied to teaching hockey players how to take better slapshots.”

Before this study, involving high-speed photography and an electronic strain gauge mounted on the stick, no one knew that the hockey stick bent when it hit the ice. Previously, manufacturers produced hockey sticks that were stiff and unyielding. Based on Roberts’ discovery, the design changed to enable the stick to load energy and serve as a spring.

Touchdown, Roberts

Another of Roberts’ research studies resulted in a discovery that changed the way football players kick field goals. Coaches had traditionally given their kickers simple instructions: “Run straight at the ball and kick it into the uprights,” Roberts says. Indeed, all but one NFL kicker at the time used that technique. Pete Gogolak of the Buffalo Bills was the lone soccer-style kicker. Roberts and one of her graduate students set out to determine the ideal kicking method.

By filming her son, as well as adult athletes, Roberts analyzed the mechanics of the kick. She learned that the power of a kick in childhood originates in a turn of the hip. However, football coaches were instructing players to change that natural movement and approach the ball head-on. Roberts proved that by advancing at an angle, soccer-style, a player could dramatically improve the speed and accuracy of the kick.

When she presented her findings at an international biomechanics conference in 1967, the news propelled her into the public eye, resulting in national press coverage.

Charlie Roberts, MD, PhD, and his parents, Betty Roberts, PhD, and Tom Roberts, PhD

Science in the kitchen sink

From his humble beginnings as a research subject, Charlie has become an acclaimed pediatric oncologist and an international expert in cancer epigenetics. He also heads the nation’s only National Cancer Institute–designated Comprehensive Cancer Center devoted solely to children. He says he attributes his lifelong fascination with science to the efforts of his mother and his father, Tom Roberts, PhD, who was also a scientist.

“I got to hear lots of science discussions between my mom and dad, because they were working together on science as I was growing up,” he says.

While his classmates were watching black-and-white TV or playing with Rock ’Em Sock ’Em Robots, Charlie and his father were involved in more sophisticated pursuits.

“I remember the two of you making hydrogen in the kitchen sink,” says his mother.

When helium balloons became the craze for kids in their neighborhood, Tom insisted that hydrogen balloons would be better.

“He brought home hydrochloric acid and some metals,” Charlie recalls. “We tested which metal was best (for the record, aluminum worked better than zinc). And in the sink, we made hydrogen balloons. Of course, they were entirely flammable. I remember putting them on the end of a fishing rod outside the house and holding them over a candle, and they would go, ‘Boom!’”

The fifth grader labeled 10 balloons and launched them from his home in Madison, Wisconsin. Another fifth grader in Rosebud, Michigan, found one of the balloons, which had completed a journey of 413 miles.

In spite of his professional accomplishments and accolades, Charlie says he considers his mom a trailblazer and scientific inspiration. She, in turn, offers simple advice to today’s girls who are considering careers in science.

“It’s just fun,” she says. “If you want to do something that’s fun and keeps you interested, there’s no end to it.”