Turn your device to return to the race!

Share this story

You liked this page. Would you like to share it with others?

Songbird

Songbird

February 8, 2020

Songbird

The little girl in the frilly dress would run through the halls of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, singing as loud as she could.

“I would sing in every part of the hospital,” Tiara Herr says now. “They probably knew I was coming because they could hear this little kid singing these cute songs.”

Nothing could silence her. Not the tumors, which would eventually number 40. Not the treatment, which would save her life but leave her legally deaf — unable to hear bird songs, fire alarms, phones ringing and the high notes on a piano.

Yet she plays piano, and writes and sings original songs. She performs in musical theater. She even gives voice lessons, drawing on a love of science sparked by St. Jude to teach singing as a “full-body experience.”

“I don’t feel like I’m missing a lot,” she says, “even though I’m missing a lot.”

The contradiction of that statement isn’t lost on Tiara. It’s her reality. It’s how she relates to the world around her. She wears hearing aids about 70 percent of the time, and says the technology has improved dramatically over the years.

“I finally found hearing aids that don’t make everything sound weird,” she says. “There were these hearing aids they were trying to fit for me. They took everything that you can’t hear and put it down to a pitch you could hear. And so I was hearing all these weird robot sounds, and I refused to wear my hearing aids. It sounded like robots in my ears and it scared the crap out of me.”

She’s also adept at reading lips. But when people are behind her and talking, she says, “it sounds like the adults from Charlie Brown.” You know, that wah-wah trombone effect used in the iconic children’s cartoon.

“Maybe I should learn sign language!” Tiara says with a smile. “But that didn’t really happen. My mom can sign a lot more than I can. But I’m working on it, I promise.”

Diagnosed as a baby and expected to die, Tiara survived only to relapse again and again. Surgery left scars she likened to railroad tracks. By age 5, she was legally deaf from the side effects of treatment.

Once, talking to Donna, her mom, about whether she was going to die, Tiara asked, “Does God have a color TV so I can watch cartoons in heaven?”

“There are so many days that go by that I forget that I went through that, that I beat cancer, so many times. And I get down on myself,” Tiara says. “Then I remember what I went through, and I remind myself that I kicked cancer’s butt so many times. And if I can get through that, I can be the strong, independent, tough lady that I am, and get through anything.”

Back home from St. Jude after treatment, she wanted to fit in, but only seemed to stick out. She was bullied because she looked different — the bald head, the brightly colored hearing aids that once were cool but now made her feel, Tiara says, “as if I was an alien.”

“I stopped wearing my hearing aids,” she says. “I stopped wanting to go to speech therapy. I stopped wanting to see the audiologist. I did not want anything to do with being deaf.”

But she drew on the strength she’d had as a little girl. She found purpose in her studies — becoming valedictorian of her high school class — and solace in her music.

And she found a place where she could be herself. She found her people.

When did she start singing? “From the time I could make words,” Tiara says.

Her late father had a beautiful tenor voice. “Oh, man, he could sing,” she says. “My dad would come in and wake us up for school, me and my sister. He would always sing, ‘School days, school days, how I love those school days.’ And we would make up words for whatever was going to happen that day.

“And my mom, actually, started teaching me several old-time songs that I’ve never heard of in modern days, but a lot of older people know.”

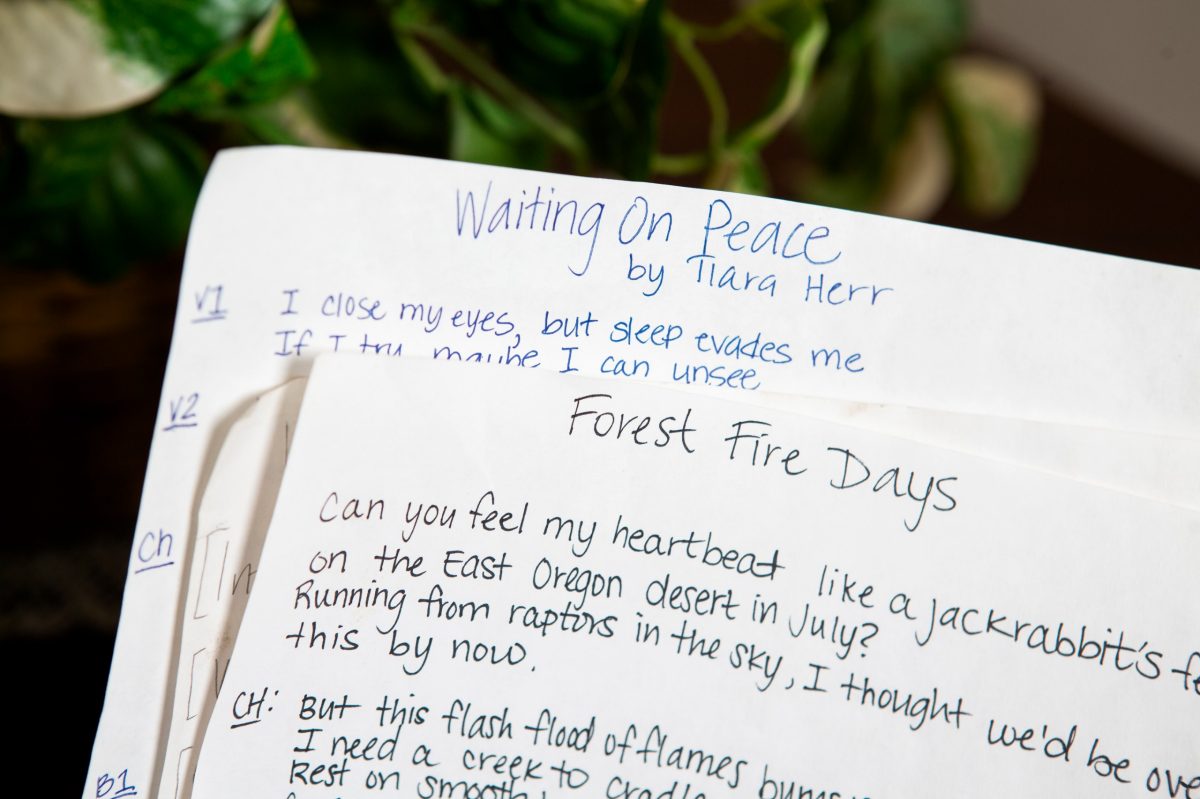

Tiara, now 28, is still singing — and writing her own songs.

“Forest Fire Days,” with lyrics based on a poem written by her sister Trinity, is about “those moments of nostalgia that always seem to catch you in a loop.”

“We always remember past times as an exaggerated version of themselves — the good times better than they were, the worst times even more terrible than they were,” Tiara says. “Nostalgia can burn you if you can’t identify fact from fiction.”

What’s a good day like, Tiara?

“A good day for me is probably a very busy one,” she says. “It starts out super-early in the morning. I wake up at 3:30 or 4 to get to work (as a research assistant in a medical lab) at 5 or 6. I work until either 2 or 4. From there I typically come home and eat something, play some music, annoy my family, and then I’ll go to rehearsal for whatever show I’m in. That typically starts at 6:30 and goes until 9. I teach voice lessons on the side, usually on a weekend day.

“And I try to play or sing as much music as I can, because that is the one thing that is guaranteed to lift me up,” Tiara says. “By singing, I’m showing everybody that my deafness doesn’t hold me back.”

Because what the little girl knew in her heart, the woman feels in her bones:

When you can’t hear a bird’s song, be your own songbird.