How Far One Mother Would Go

How Far One Mother Would Go

St. Jude Global launched in May 2018 to train clinical staff in hospitals and clinics around the world, share cutting-edge research, and strengthen partner health systems so even more children receive quality care across the globe. At ALSAC, the fundraising and awareness organization for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, we teach foundation members of The Global Alliance best practices in fundraising, marketing and communications. There are more than 100 hospitals and clinics, and 50 foundations in 57 countries that participate.

Natalia Vilcu is president of one of those member foundations, Life Without Leukemia, in Moldova. website is viatafaraleucemie.md

This is her story.

podcast.

Part 1Racing time, fearful mom crosses a border to solve medical mystery as her son grows ill back home in Moldova

An hour before midnight Natalia Vilcu boarded a bus in Chișinău, the capital city of Moldova. The all-night trip across the Romanian border was one she’d taken before. This clear September night in 2019 the bus was crowded with college students headed back for their fall semester. It was her mother’s 69th birthday, and she dozed in the seat next to Natalia. But Natalia felt unsettled, her body electrified with worry. This trip was nothing to celebrate.

She prayed.

God, please make everything to be good. Arrange things in such a way that everything ends well.

Natalia clutched a black backpack in her lap, careful not to jostle or bang it. Only she and her mother knew what was hidden inside: A test tube wrapped in aluminum foil. Inside it was her 13-year-old son Gheorghe’s bone marrow.

She had 12 hours to get to a lab in Bucharest before the sample was no longer viable.

The bus bumped along two-lane roads through villages, past corn and soybeans fields, the only crops not ready for harvest. Natalia worried about the driver’s speed and whether there’d be an accident. There were so many in the villages late at night.

She worried how long it would take to cross the border.

There was no time to waste.

Gheorghe had been diagnosed with cancer and treated, but he’d shown signs of relapse. The first test in Moldova showed the cancer was back. The second, that he was clear.

Labs in Moldova use older methods — cells under a microscope analyzed by the human eye. Sometimes there’s error. Sometimes the answer isn’t clear. Natalia and her husband, Ruslan, wanted a more sophisticated analysis, one from a machine called a flow cytometer. But there wasn't one in all of Moldova, a landlocked nation between Romania and Ukraine with a population of less than 3 million. The closest one was in Bucharest, 270 miles away. Seven hours in the best conditions.

The sun rose just before the bus pulled into Bucharest, a half hour before the lab opened.

She made it in time. The third and final trip her family would make for Gheorghe.

When the doors opened, Natalia handed the test tube to a nurse. The results would come by email.

She’d have to make the long trip home and wait.

Part 2Something is wrong: Gheorghe isn't his opinionated self

Gheorghe had always been different from his twin brother, Andrei. Never studious or patient, he had his own way of doing things. He was so direct he couldn’t lie, his mother said. He was an artist, a painter who kept his own pace – a boy with plenty of opinions.

Doctors diagnosed Gheorghe with a seizure disorder when he was 9. It stayed under control with medicine. But in March 2018, he was more sluggish than usual. He didn’t want to go to school, do his homework. He refused any physical activity. He wouldn’t get out of bed.

At first, Natalia thought Gheorghe was lazy, always comparing him to his twin. But then he developed small bruises on his hands and legs. Something was wrong. He needed a doctor.

Gheorghe at a school fair.

In the emergency room, Gheorghe’s platelet count was critically low. They admitted him. But nobody knew what was wrong.

The first set of doctors said it could be his liver. Another suggested his throat. Maybe rheumatism because he had pain in his legs. His heart, perhaps.

Natalia thought possibly an overdose of epilepsy medication. But the neurologist said medicine wouldn’t cause this type of acute illness.

For six days, Natalia and her husband waited for answers. Doctors gave Gheorghe blood transfusions to keep him alive. All that time he was alone. In Moldova, once children reach the age of 6 they aren’t allowed to have a parent stay with them in the hospital.

It’s just the rule.

Natalia’s only pass to see her son was when she brought his epilepsy medicine.

She saw him 20 minutes a day.

“It’s extremely painful,” Natalia remembered. “And emotionally – now I understand it hurt him emotionally maybe more than medically.”

Gheorghe was deteriorating. Doctors decided to take a bone marrow sample. But if Natalia wanted the results that day, she’d have to deliver the microscope slide to the lab herself.

By 1 o’clock.

It was almost noon.

The lab was on the other side of town. And the city’s recent March snowfall had snarled traffic.

Natalia raced to the oncological hospital, a building she’d averted her eyes from her entire life. She’d always been afraid of cancer. No one talks of cancer in Moldova. The word is so taboo that people don’t think of it, much less speak it. Even those who’ve had the disease don’t mention it for fear they might call it back into their lives.

Not for one second in those six days of waiting did Natalia consider the possibility for Gheorghe.

Children with cancer could not be treated. Certainly not in Moldova. They died. And if there was any chance at all, they’d have to go to another country for treatment. The family would have to sell its flat, the car, and use every bit of savings. That’s what Natalia believed. This educated woman with a law degree who worked for the country’s constitutional court.

Gheorghe (left) and his twin brother, Andrei (right) on a family vacation.

Part 3Doctors know young Gheorghe has cancer, but what kind?

Gheorghe’s diagnosis came in two blows.

He had leukemia. And doctors weren’t certain which kind.

There’s acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). And acute myeloid leukemia (AML). But the treatment protocols are different.

Doctors believed there was a strong indication Gheorghe had AML – the one with the lower survival rate. It’s the best they could offer with the equipment they had.

Gheorghe and his sister, Ana, at her birthday in the midst of final stage of treatment.

But how to be sure? What if doctors treated him for the wrong type?

Cancer treatment for children in Moldova is free under the government healthcare system, but doctors don’t always have access to certain types of medication or sophisticated analysis available in other countries.

The state simply can’t afford it.

Parents can bring in medication from other countries they trust. Or take their children – or lab samples – out for tests. But they’re responsible for the bill.

There was a machine in Romania that could give a more accurate picture, doctors told them. But they were on their own to get the sample there. And they'd have to pay for it.

At 9 p.m. on April 1, Gheorghe’s dad, Ruslan, waited at the hospital door for the test tube with his son’s bone marrow. He drove all night and slept in his car until the laboratory opened in Bucharest. It would be the first of three trips to Romania his family would make for Gheorghe.

Gheorghe (right) and his brother, Andrei (left) before the final stage of treatment.

He cried on the phone to his wife.

“Natalia, you know the doctor said the analysis will be ready in 10 days. I don’t know what to do.”

Natalia told him: “What do you want me to do? You are there. Go and find the doctor. Ask him to make the analysis as quickly as possible.”

Gheorghe’s condition was not improving. At least now Natalia could stay with her son. A cancer diagnosis was the one exception to the age rule.

But without the results, doctors in Moldova couldn’t start treatment. Which protocol to use? ALL? Or AML?

Gheorghe’s life hung in the balance.

Gheorghe and his family on vacation.

Part 4'God's present for his birthday'

All Gheorghe could think about was getting out of the hospital to celebrate his 12th birthday.

"Give me 10 pills, and I will go home,” he declared.

But Gheorghe needed more than pills. He had cancer.

Natalia didn’t explain his diagnosis. The name of the disease didn’t matter. Gheorghe wouldn’t have understood anyway. He was just crushed when doctors told him treatment would last for months. He couldn’t go home. And no one could visit his hospital room.

Natalia’s own worry simmered. She checked email over and over for the results of the bone marrow analysis from Romania.

Was it ALL or AML?

Doctors needed the answer to start treatment.

Finally, the day after Gheorghe’s birthday, the results arrived. It was the first bit of good news they’d had.

Gheorghe celebrates his birthday in the hospital.

Yes, Gheorghe had leukemia. But it was ALL, after all. Not AML as doctors in Moldova had suspected. He had the disease with the better chances of survival.

Doctors could start treatment.

“I said it was like God’s present for his birthday,” Natalia remembered.

But the following months proved a monumental test of endurance.

Four patients and four parents stayed in one room in the cancer unit. Natalia either slept in Gheorghe’s bed or on the floor. There was always crying or complaining. Someone wanted to listen to music. Someone wanted to sleep.

Gheorghe was impulsive and stubborn. He hated hospital rules. He was sick from the chemotherapy. He threw up, suffered diarrhea and lost his hair. He missed home.

But the treatment was working. It was killing the cancer.

Gheorghe made it to the second stage of treatment. And then the third.

But all this time, Natalia was terrified. She had little support and often couldn’t get enough information from doctors. They talked strictly about treatment, nothing else. Not because they didn’t want to but because they didn’t have time.

They didn’t offer referrals for a psychologist or explain the side effects of drugs. They sometimes referenced treatment not available in Moldova.

Natalia found herself fishing for answers:

“What is this? Where can I find more information about this? Or, if my child is feeling like this, is it ok?

Is it not ok?”

She was clever enough to find information and met with other moms to press the hospital.

The hospital administration, for example, referred to some investigations that weren’t available in Moldova.

“We were asking why we don’t have this equipment?” she said. “Or why we cannot have this analysis performed in Moldova.”

“Why cannot the hospital buy these (quality) medications? That every parent has to buy it with his own money and to bring it to hospital?”

In December 2018, Natalia joined two moms who ran a volunteer association called Life Without Leukemia. It was the same time the group connected with ALSAC, the fundraising and awareness organization for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in the United States. They had a program called the Global Alliance that connects hospitals and clinics all over the world with experts at St. Jude. And it brings together foundations in other countries that support those hospitals with ALSAC to learn fundraising from the world's largest healthcare charity; an organization that faced many of the same challenges when it began its work in the U.S. 60 years ago.

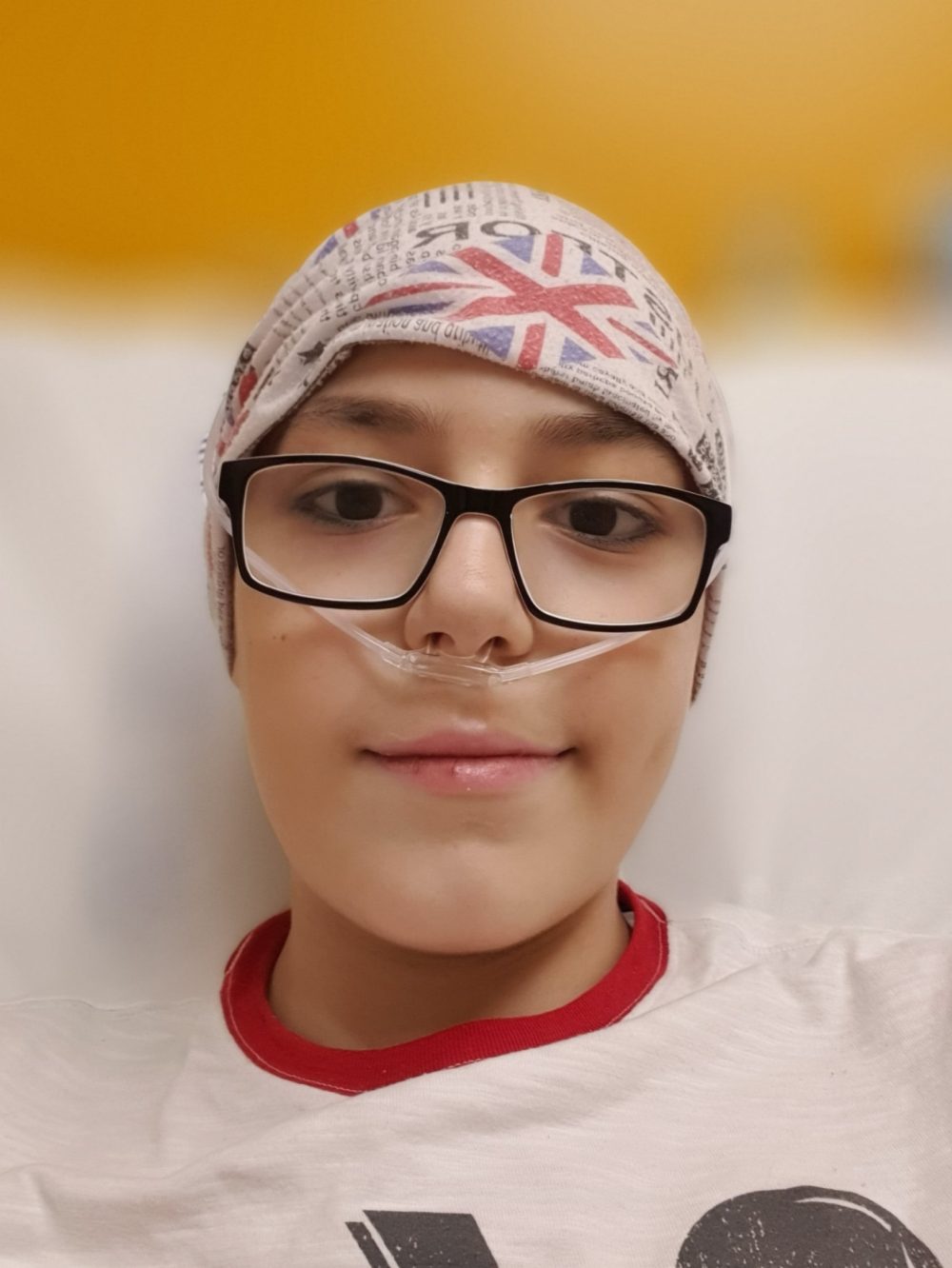

Gheorghe.

Natalia was named president of Life Without Leukemia in January 2019, the same month her son Gheorghe was discharged from the hospital.

The new year seemed so full of promise.

“I was so naïve,” she remembered. “I thought that by the end of the year I would change everything.”

The next month, on a cold February night, Natalia boarded a bus at the central station in Chișinău. It was her turn to travel. Alone. In her backpack were two vials of bone marrow wrapped in aluminum foil. One was her son’s. The other was of his friend's.

They’d both finished treatment. Gheorghe by a month. The friend, two years.

Both moms wanted to know the disease was gone — obliterated from the bodies of their beloveds.

Natalia wrapped her coat and scarf tight. There was no heat on the seven-hour ride to Bucharest or the return trip home.

Within days, the results arrived: Gheorghe and his friend were cancer free.

Natalia was elated but somehow not relieved.

She couldn’t have fathomed the heartache to come.

Sightseeing after treatment, April, 2019

Part 5'These are the days I can hardly remember'

By August 2019, Gheorghe’s blood work didn’t look good, so doctors wanted to check his bone marrow again. At that time, Natalia thought a relapse would be the end of the world.

The fear she’d had since Gheorghe’s initial diagnosis arrived: Test results showed signs his leukemia had, in fact, returned. That was on a Friday.

But doctors weren’t convinced the test was right. They’d do another one Monday.

Gheorghe.

The weekend wait seemed interminable. And Natalia trembled as she drove to the hospital that Monday morning. But when the doors swung open, relief flooded her heart when she saw the doctor’s face. The numbers were good. Gheorghe would be alright.

Natalia sobbed. She called everyone who knew their struggle through these last few days of unbearable uncertainty. The family planned a three-day vacation to the mountains in Ukraine to celebrate.

But something gnawed at Natalia. She couldn’t admit to herself there’d been a mistake. What if the first test had been right all along? She had to be sure, and there was only one way to know the truth.

She’d have to go back to Romania, this time with her mother at her side for the long bus ride.

“You always think things cannot be worse,” Natalia said. “But in our case, particularly at the end of September – these are the days I can hardly remember. I don’t want to remember.”

What Natalia hadn’t told Gheorghe was that this third trip to Bucharest was one that not only held the truth of his diagnosis — but her own.

After Natalia dropped off the test tube with Gheorghe’s bone marrow for analysis, she met a doctor at another clinic across town who broke the unexpected news:

Natalia had breast cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes.

She sat in a park on the hospital grounds and worried aloud to her mother. Ana, her oldest, would be alright. Andrei would, too. But who would take care of Gheorghe if something happened to her? His medications, appointments.

Natalia couldn’t wrap her head around it.

She had to get home to her son.

Part 6One final trip: No possible cure for Gheorghe at home in Moldova

It had been six days since Natalia and her mother traveled to Romania for the final time. And the results from the bone marrow analysis were still not in. Gheorghe was getting worse by the hour, not the day. Natalia didn’t blame anyone. Other countries have their own protocol, their own rules.

Gheorghe Vilcu was just another name in the queue.

But doctors in Moldova didn’t want to wait any longer. They decided to take another bone marrow sample. This time, there was a clear indication of relapse. Gheorghe needed a bone marrow transplant. And that wasn’t possible in Moldova.

Gheorghe painted pictures to give as presents for his doctors and nurses.

In Moldova, as in other post-Soviet countries, everyone is responsible for his own life. If Natalia wanted something better than what the state was offering, she knew she’d have to make her own way. She abandoned all her work with Life Without Leukemia to save her own son. She asked her colleagues to do their best to keep everything afloat.

Natalia and her husband decided to try to get Gheorghe to Italy. It was his only chance to survive.

They prayed his condition would improve enough that he could fly.

Once she got him settled, she’d think about her own cancer treatment. Doctors said she, too, had no time to lose.

Natalia doesn’t remember having time to eat or drink. She was constantly on the phone. She had to buy plane tickets, arrange Gheorghe’s travel documents, find someone to take care of her other children.

Natalia thought these must be the most difficult moments of her life.

But they were not.

Those days were to come.

Within five days, Natalia had everything arranged. On September 22, Gheorghe boarded a 7 a.m. flight, and by 11 a.m., he was in a hospital emergency room in Torino.

All his organs were enlarged — liver, kidneys and his heart. He didn’t urinate for 26 hours.

Because Gheorghe was retaining so much fluid, the 13-year-old weighed 180 pounds.

After 10 days of intensive treatment, doctors stabilized him. And by October 5, Gheorghe was strong enough to start chemotherapy again. Doctors were optimistic they could perform a bone marrow transplant. His sister, Ana, would be his donor.

On the third day of Gheorghe’s chemotherapy treatment, he started to cough. Tests showed he had a fungal infection in his lungs. But doctors treated it and every 10 days ordered a new scan. He was stable.

Gheorghe was still persnickety, complaining once that a nurse couldn’t give him a shot because he didn’t like her teeth. He painted to pass the time, mostly nature scenes he gave away to nurses and doctors he liked. He mixed a blue and purple palette on a black-as-night background with white flecks of twinkling stars — the cosmos. This one his mother kept.

Having Gheorghe settled meant Natalia could turn her attention to her own treatment. She’d make the round trip to Romania and back — by bus then plane — within 48 hours before the side effects from her chemotherapy got too bad.

She grew closer to her son through their shared experience — bald heads, stomach pains and diarrhea. But true to his personality, Gheorghe still couldn’t lie: She looked better with a head scarf than without.

Natalia had steered her son clear of seemingly every obstacle.

Until November 20.

Part 7'I will fly to the cosmos.'

Gheorghe’s most recent scan showed the fungal infection had spread, and the cancer was roaring back. His body could no longer resist. Doctors would make him comfortable.

Natalia called her mother. She wanted the whole family to fly in for Christmas. To spend time with Gheorghe. Orthodox Christians celebrate the holiday January 7. But when in Italy, they’d celebrate the Italian way — around December 25.

Gheorghe in the hospital.

Piled in a two-room hospice apartment in Torino, Gheorghe told stories and fiddled with all the filters on his new phone. He chattered on about the Italian soccer players who’d visited the hospital several days before. He played with his brother. He told stories.

It was hard for him to walk and breathe.

For Natalia, it was inconceivable that she could leave the room at any minute and come back to find her son no longer smiling at her.

On Saturday night, December 21, Gheorghe had his bath and put on new pajamas — a Christmas gift from grandma. He sat on the bed, cross-legged, like a sultan.

For the moment, Gheorghe and Natalia were alone. His words bubbled up, unexpected, like a confession.

“You know, mom, you love me so much, and I love you so much,” he told her. “For me, we will always be No. 1.”

Natalia protested. There were so many people in his life to love: Daddy, Grandma, Ana — even his twin, Andrei. But Gheorghe persisted. She had given him everything he wanted in this life.

“I received everything I wanted, and now I will probably fly to cosmos,” he said.

Natalia was incredulous. She would finish her treatment. Gheorghe would finish his. They would go home.

“No,” he said. I will fly to cosmos.”

Then Gheorghe started to sing the chorus “We are the Champions” by Queen — his sister’s favorite band. He was as much a singer as a reader. That is to say neither.

But he was calm, peaceful. And he laid down in the bed.

That was their last conversation.

In middle of the night, he had a breathing crisis. Doctors increased his sedation and pain medication. He wasn’t afraid or suffering. He slept all day December 22.

On December 23, at 9 o’clock in the morning, Gheorghe’s heart stopped beating.

Part 8A mother's vow: Natalia devotes her life – 'as long as it may last' – to other Moldovan kids with cancer

Natalia’s final wish was to bring Gheorghe home before the turn of the new year. They made it. 10 p.m. December 31.

Natalia didn’t want to bury Gheorghe in Chișinău, at St. Lazarus, one of the largest cemeteries in Eastern Europe. His final resting place might be lost in a sea of hundreds of thousands of graves. So, on January 2, the family held a funeral service and buried Gheorghe in a cemetery in Edineț, nearly three hours outside Chișinău, Natalia’s parents’ hometown. Neighbors lined the street.

In the days that followed, Natalia was engulfed with grief and consumed with the answer to one question: Where did we make a mistake?

She traveled back to Romania on Orthodox Christmas Day for chemotherapy.

She was exhausted and told her colleagues at Life Without Leukemia she couldn’t continue. For the mission she’d fought so hard to promote, she was giving up.

Natalia was surprised by their reaction. They were prepared to follow her, they said, but not to lead. Volunteers like Irina Rotari loved to help. But Natalia was the lifeblood. She was a force that simply kept on even when people said no.

Natalia and Gheorghe.

“She’d say, ‘Ok, we’ll try. We’ll resolve. We’ll solve. We’ll do it. We’ll think of how,’ Irina said. “But not no. Never no.”

Without her, Life Without Leukemia would dissolve.

Still, Natalia was unsure of her own prognosis. She was so sick from chemotherapy she couldn’t make it to the breakfast table. She wanted to spend as much time with her family as she had left.

But the memories were too painful to keep reliving alone in her bed. And she could scarcely stomach the thought everything she’d worked for would be lost. So, she made a vow:

“I will devote the rest of my life, as long as it may last — a year, 10 years, 40 years, I don’t know how much. But I will try to continue what I have started. And to make this association have a very loud voice in changing things.”

She wanted a team, a strategic plan. They needed a campaign to press the hospital for better equipment, renovation of the pediatric unit, and stronger communication from doctors. But they would work together, not as adversaries.

Natalia got more involved with ALSAC in the United States. She never missed a monthly call, a training session, a webinar even as she received treatment for cancer in Romania.

It was like breathing new air — like dreaming awake.

Natalia still wasn’t being paid as head of the association but hired Irina Bordeianu, another patient mom who came from an international advertising agency in Moldova.

Irina created branding, reached out to media and, this year, launched a campaign called “I want to be treated at home in Moldova.” The association’s manifesto highlighted one of the most pressing problems for pediatric cancer patients in the country: limited access to early diagnostics.

So, Life Without Leukemia would make it a priority. The organization would raise money on its own to buy a flow cytometer — the machine Gheorghe’s family had traveled to Romania for so many times.

They raised 70,000 Moldovan leu, but it would take 2.6 million to buy one.

That’s $148,000 U.S. dollars.

Natalia and Irina went on television, granted interviews to newspaper reporters. Life Without Leukemia stayed in the press.

Then, in August, Natalia received an unexpected phone call. The cancer hospital in Chișinău had decided to allocate money to buy that machine.

Natalia couldn’t believe it.

Gheorghe's family plants a tree in his memory.

But there on the government website she saw the request for bids. Procurement number 21042696.

The third item on the lot list was the flow cytometer.

Natalia Vilcu never lost her voice — even after she lost her son.

And now because of that untold numbers of moms and dads who traveled by bus to Romania with test tubes wrapped in aluminum foil to have their children’s bone marrow analyzed won’t need to make that desperate journey any longer.

Because by next year there’ll be a flow cytometer in Chișinău.

Next year, their children can be diagnosed and treated at home.

At home in Moldova.

Postscript: Natalia finished chemotherapy in February 2020 and radiation therapy later that year. She continues to have regular health checks in Romania, which show her condition is stable.

Gheorghe on a short family vacation...the last one.